The First 000 Years

Presented by

Explore Episodes

![The Marquee]()

Play Episode

Episode 1 | 9:26

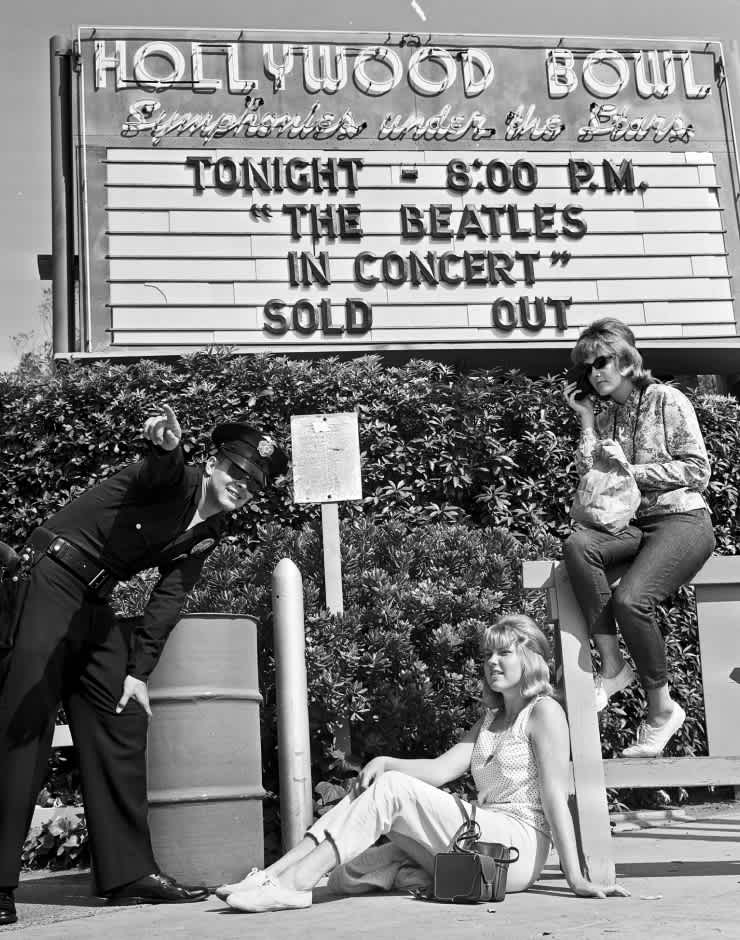

MARQUEE

Seeing your name on the Hollywood Bowl marquee is one of the milestones signaling you...

![Muse of music]()

Play Episode

Episode 2 | 7:21

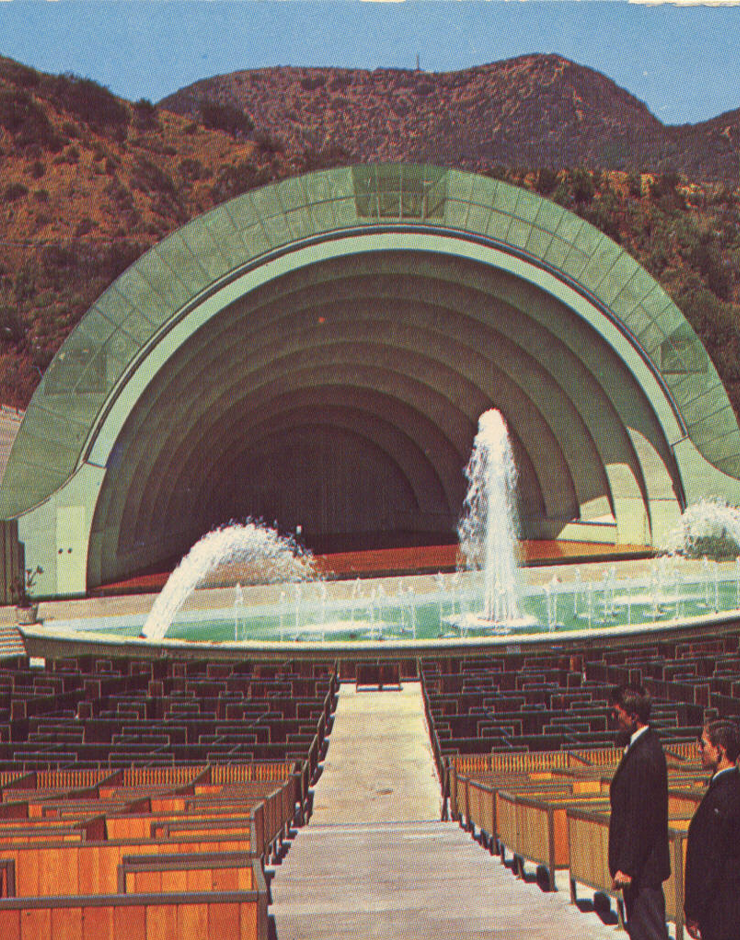

MUSE OF MUSIC

Born of the Great Depression and nearly lost to disrepair, the fountain complex has s...

![Episode cover]()

Play Episode

Episode 3 | 7:28

PEPPER TREE LANE

Pepper Tree Lane—the walkway that transports you to the Bowl—is named for the trees t...

![Tea Room]()

Play Episode

Episode 4 | 5:35

TEA ROOM

For decades, the Hollywood Bowl’s tea room and gardens were a gathering place as mean...

![Hollywood Bowl Shells]()

Play Episode

Episode 5 | 7:37

HOLLYWOOD BOWL SHELLS

From controversial choice to celebrated symbol, the Hollywood Bowl’s historic shells ...

![The Pool Circle]()

Play Episode

Episode 6 | 6:06

POOL CIRCLE

Of all the experiments in the Bowl design over the last century, none has inspired mo...

![SEATING AREA]()

Play Episode

Episode 7 | 8:22

SEATING AREA

Whether you prefer a box or a bench, the Hollywood Bowl experience has been a beloved...

![Backstage]()

Play Episode

Episode 8 | 7:33

BACKSTAGE

Before the current shell was installed in 2004, backstage at the Bowl was more greene...

![The Park]()

Play Episode

Episode 9 | 8:46

THE PARK

The Hollywood Bowl is an 88-acre Los Angeles County Park, filled with picturesque hid...

![]()

Play Episode

Episode 10 | 12:13

NAMED SPACES

Only a handful of truly devoted Bowl fans have been honored with a space named after ...

Signage depicting the Lawrence N. Field Gate at the Hollywood Bowl

Photo Credit

Los Angeles Philharmonic

Entrance to The Ford, across Highland Avenue from the Hollywood Bowl

Photo Credit

Los Angeles Philharmonic

Supervisor John Anson Ford sits at a desk with a bouquet of flowers, 1930s

Photo Credit

Lost Angeles Daily News Negatives, UCLA Library Special Collections

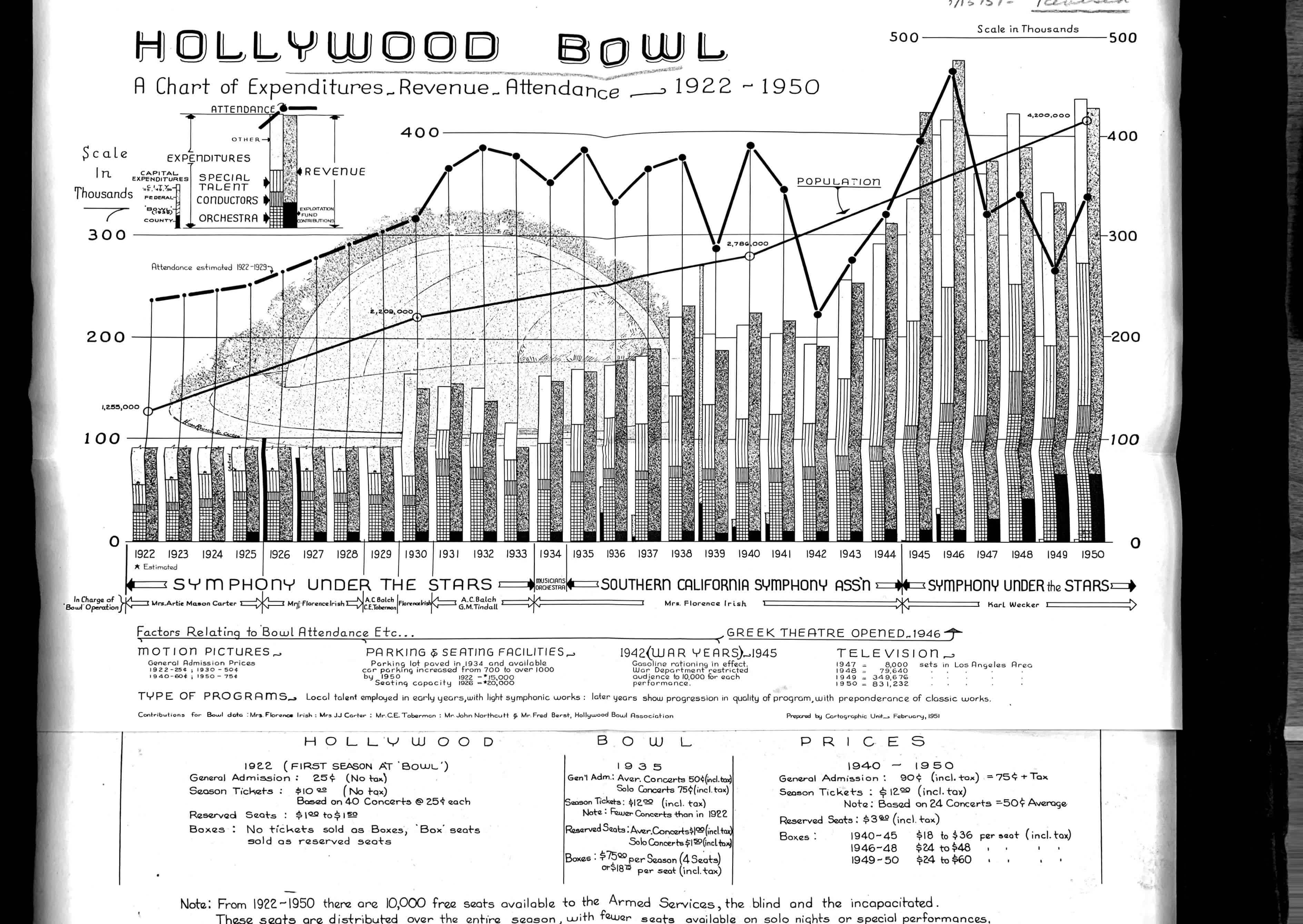

Infographic with detailed Bowl figures requested by Supervisor John Anson Ford in 1951

Photo Credit

The Huntington Library

Bowen "Buzz" McCoy conducting "The Star-Spangled Banner" at the Hollywood Bowl on Opening Night, June 25, 1999.

Photo Credit

Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives

Buzz McCoy in front of plaques honoring his and Royce Diener’s leadership at the Bowl

Photo Credit

Timothy Norris

Olive Behrendt, chair of the Philharmonic Board, 1976-1977 with Zubin Mehta.

Photo Credit

Ralph Samuels, courtesy of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives

Behrendt sweeping out the boxes before patrons arrive for an Opening Night concert.

Photo Credit

Los Angeles Philharmonic

A sample “Your Name Under the Stars” plaque at the Hollywood Bowl

Photo Credit

Los Angeles Philharmonic

Seat-naming donor Dianne Waldman posing with her named bench seat. Her plaque reads: "Dianne "Dijou's" L.A. Happy Place."

Photo Credit

Los Angeles Philharmonic

1/10

The Hollywood Bowl would not exist without the driven leaders, volunteers, and benefactors who have spent the last century building the Bowl from a dusty canyon with uncanny acoustics into the world-renowned venue it is today.

A handful of those Bowl champions have been recognized with what we call “named spaces.” You might have noticed signage cropping up in the last few years – Chao’s Popcorn, Ann’s Wine Bar, and The Lawrence N. Field Gate, for example. Behind each one of those names is the story of a truly passionate, committed Bowl superfan. Their stories are some of the most moving and most powerful in the Bowl’s 100-year history.

We’re going to start not at the Bowl but at its sister venue, across the street, the Pilgrimage Playhouse, which in 1976 was renamed the John Anson Ford Amphitheater, or simply The Ford.

John Anson Ford was one of the most powerful people in the history of Los Angeles. As a County Supervisor from 1934 to 1958, he helped shape the city in profound ways. In his time, he was popularly known as “Mr. Los Angeles.” When he was first elected, Ford was a bespectacled, bow-tie-wearing newspaperman who admitted he knew nothing about the arts and cared about them even less.

But, when you dig into Ford’s papers, which are archived at the Huntington Library, they show how over time he developed a deep passion for the arts and an almost obsessive interest in the Hollywood Bowl. If management increased the price of hotdogs by a nickel, Ford would write them a letter asking why.

In 1951, in honor of the Bowl’s 30th season, Ford collected every bit of data about the Bowl’s history: attendance records, sales figures, expenses broken down by minute categories, the number of artists presented each year, etc. He then asked the County’s Cartographer Hugo Rauch to turn it all into an enormous wall-sized infographic that Ford hung in his office.

So, what changed Ford’s mind about the arts? His son, John Arnold Ford. John Arnold had been a poor student all his life and in the 1930s was a directionless teenager who showed little motivation or interest in anything in life. That was until his high school music teacher discovered John Arnold had an impressive bass singing voice. Once he had found his calling, everything changed for the younger Ford, who grew up to be a highly successful opera singer.

When John Anson Ford saw what music could do for a young person, how it could turn their life around, he knew he had to do everything in his power to make music accessible to everyone. And the best way to do that, he decided, was to become a champion of the Hollywood Bowl.

If you’re a Bowl regular, you’ve probably found your way to Buzz McCoy’s Marketplace. It’s the small store where you can buy food, wine, or snacks on the west side of the venue, off of stage right.

Buzz, short for Bowen, is in his 80s now, and is approaching his 40th year as a leader on the LA Phil’s Board. When he joined, he told management: ‘I don’t want to just want to sit through meetings, put me to work!’

They did. Over the next couple of decades, Buzz was one a few key leaders who literally transformed the Bowl. He championed a County Bond Measure to raise funds specifically for public lands, museums, parks, and the arts. McCoy helped rally Los Angeles and its politicians around the Measure, saying: “I don’t care if you’re a Republican or a Democrat. I WANT TO REBUILD THE HOLLYWOOD BOWL.”

The bond measure passed and through it and its successors, the County has allocated $1.6B, that’s Billion with B, to projects for the public good, including tens of millions of dollars for the Bowl. With those funds, we completely rebuilt the shell in 2004; we replaced every seat in the theater; we installed high-def video screens, and we greatly expanded the restrooms, adding the red light / green light system over the stalls. Buzz is particularly proud of that innovation.

As a thank you for his service, the LA Phil asked Buzz to conduct the Star-Spangled Banner before a concert in 1998. In rehearsal, the orchestra was sluggish and unresponsive, and McCoy was terrified of what would happen when he walked out to conduct in front of 12,000 people. But, at the concert, the orchestra were totally with him – he had passed his initiation; and in performance they made him look like a pro. He said it was the thrill of a lifetime.

The third name I want to talk about has actually disappeared from the Bowl and from Bowl history, largely. Like Buzz McCoy, Olive Behrendt was a philanthropist who didn’t just want to attend meetings and parties, she wanted to be put to work.

Behrendt was born in 1915 in Alhambra, CA. As a teenager, she excelled as a singer, landing a position with the San Francisco Opera, before she gave up her career for her marriage, which brought her back to Los Angeles at age 23. Behrendt spent the next 50 years of her life as a leader working in the arts. She was Dorothy Chandler’s right hand in building The Music Center; she led the Board of USC’s Music School; and she helped found the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where she created a Sunday chamber music series that’s still running today.

But Olive’s first love was the Hollywood Bowl and its musicians. She was a fixture at almost every concert, all summer long. As a philanthropist and sophisticated socialite, she’d often share her box with her celebrity friends: Anne and Kirk Douglas, Danny Kaye, Gregory Peck, Gregor Piatigorsky, even the notoriously dour and introverted Jascha Heifetz who absolutely loved her–the two would play jazz piano duets together.

For all the glamor in her life, Olive Behrendt never lost touch with her roots as a kid from Alhambra. She was grounded, cool, effortless in her charm. In a Bowl era when patrons would bring elaborate picnics with candelabra and crystal glasses, Behrendt was famous for eating a corned beef sandwich out of a brown paper bag. I found a photo of her from a Bowl Opening Night in the 1980s, where she’s wearing this elegant sleeveless dress, while she carries one of those enormous push brooms, so she can sweep out the boxes before everyone else arrives.

She loved the musicians of the orchestra, and the feeling was mutual. At the end of every season, she’d host a concert to raise money for the musicians’ Pension Fund. She and her husband kept a second home in Venice, where she became the first woman in the history of the city to be granted a power boat license. When the orchestra went on tour to Italy, she’d take the musicians out on her motorboat, four at a time, flying through the canals at breakneck speed.

Behrendt became the first person to have her Hollywood Bowl box dedicated to her. A silver plaque with her name on it was installed, a gift from the musicians for whom she had done so much. We’ve since replaced the boxes, and Olive’s plaque has long since disappeared, but I think it might be time to put it back.

Naming opportunities at the Bowl aren’t just for individuals, and they aren’t just given to physical spaces – they can also be tied to performances, like the KCRW Festival, which has brought world music to the venue for more than two decades.

In May of 2021, the Hollywood Bowl had not hosted a live audience for nearly 600 days, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. That spring, as the vaccines rolled out, and the performing arts took their first steps toward reopening, the Hollywood Bowl began gearing up for the most longed-for concerts in its history.

Given all the uncertainty of that time, we started small: capping attendance at 25% of the venue’s size and requiring masking and physical distancing between audience members. And—in the egalitarian, open spirit of the Bowl—the first shows back were offered free of charge to the healthcare workers and first responders who had done so much to hold Southern California together through such difficult times.

Kaiser Permanente stepped up as a title sponsor for the May concerts. By lending its name to the proceedings, Kaiser inspired confidence for those of us working and attending those shows. Kaiser’s name on the digital screens was like a beacon, signaling that we could all return safely.

Gustavo Dudamel summed it up best: "It was maybe the purest musical experience I’ve had in the Bowl, or anywhere.” he said, “That first chord—we were in tears. The music was very tender, but there was also such a power in it—proof that we as a group of human beings could move forward.”

Today, Kaiser Permanente has become the Official Health and Harmony Partner of the LA Phil—a meaningful way to commemorate the role Kaiser played in a pivotal moment in Bowl history, and a testament to our shared belief in the healing power of music.

One thing I love about the Bowl is that every summer, when you come back, there is something that’s changed. A fresh coat of paint, a different food stand, an entirely new bandshell, you just never know. This summer, we’ve done extensive work to the inside of the shell and the stage below it, which really hadn’t been touched since it was installed in 2004.

You also might have noticed that we’ve added hundreds of new names, all on commemorative plaques installed outside boxes and on the backs of benches. Starting at $500 for a seat in the back of the house, donors can give a gift and name a box or bench in honor of themselves or a loved one.

We call it the Your Name Under the Stars campaign—which is a riff on the Bowl’s first classical series: Symphonies Under the Stars. Okay, full disclosure, I came up with that name, and I’m super proud of it, because it speaks to the shared nature of the Bowl’s legacy.

The Hollywood Bowl has thrived for a century because of all the people who love the place and have stepped up, in ways large and small, to support it. The Bowl’s first 100 years end this summer—but its next 100, the chapter of the story we get to write—is just beginning.

0:00

0:00