The First 000 Years

Presented by

Explore Episodes

![The Marquee]()

Play Episode

Episode 1 | 9:26

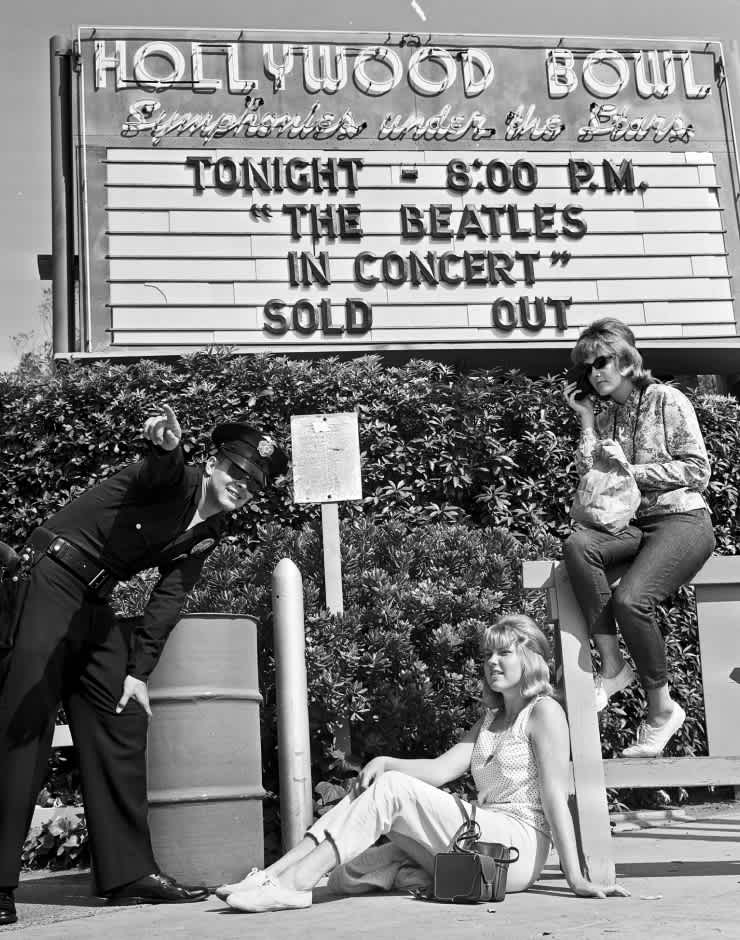

MARQUEE

Seeing your name on the Hollywood Bowl marquee is one of the milestones signaling you...

![Muse of music]()

Play Episode

Episode 2 | 7:21

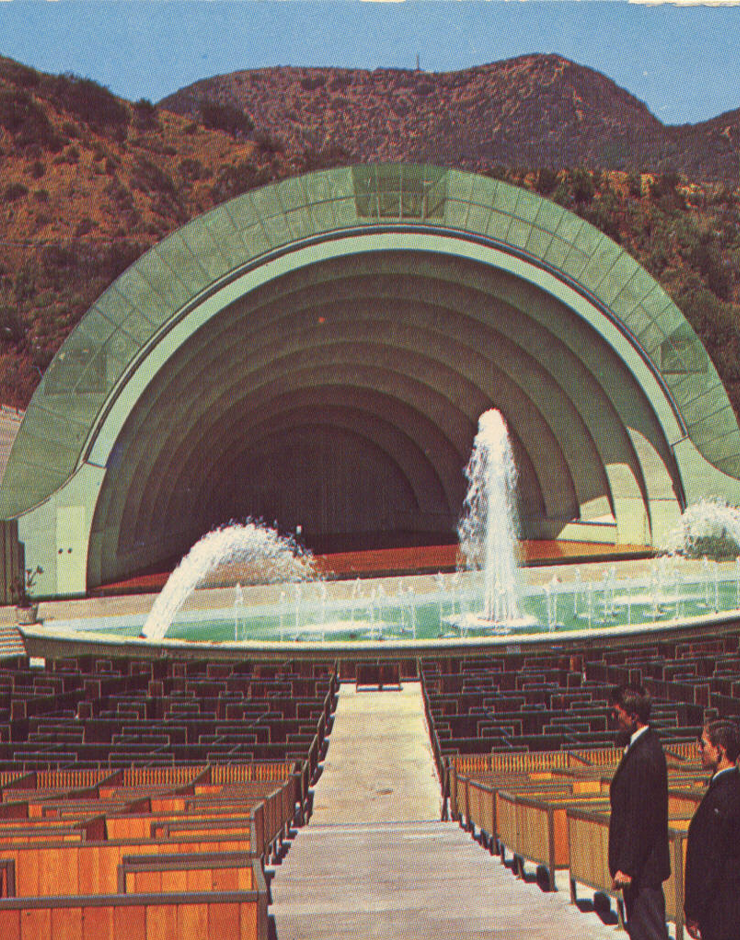

MUSE OF MUSIC

Born of the Great Depression and nearly lost to disrepair, the fountain complex has s...

![Episode cover]()

Play Episode

Episode 3 | 7:28

PEPPER TREE LANE

Pepper Tree Lane—the walkway that transports you to the Bowl—is named for the trees t...

![Tea Room]()

Play Episode

Episode 4 | 5:35

TEA ROOM

For decades, the Hollywood Bowl’s tea room and gardens were a gathering place as mean...

![Hollywood Bowl Shells]()

Play Episode

Episode 5 | 7:37

HOLLYWOOD BOWL SHELLS

From controversial choice to celebrated symbol, the Hollywood Bowl’s historic shells ...

![The Pool Circle]()

Play Episode

Episode 6 | 6:06

POOL CIRCLE

Of all the experiments in the Bowl design over the last century, none has inspired mo...

![SEATING AREA]()

Play Episode

Episode 7 | 8:22

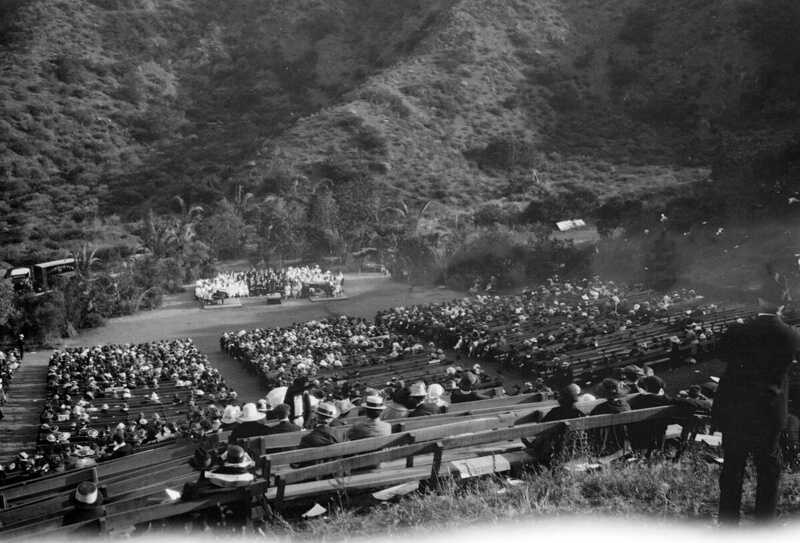

SEATING AREA

Whether you prefer a box or a bench, the Hollywood Bowl experience has been a beloved...

![Backstage]()

Play Episode

Episode 8 | 7:33

BACKSTAGE

Before the current shell was installed in 2004, backstage at the Bowl was more greene...

![The Park]()

Play Episode

Episode 9 | 8:46

THE PARK

The Hollywood Bowl is an 88-acre Los Angeles County Park, filled with picturesque hid...

![]()

Play Episode

Episode 10 | 12:13

NAMED SPACES

Only a handful of truly devoted Bowl fans have been honored with a space named after ...

Fireworks and smoke above the Bowl’s shell with a marching band on stage

Photo Credit

Photo by Adam Latham / Los Angeles Philharmonic

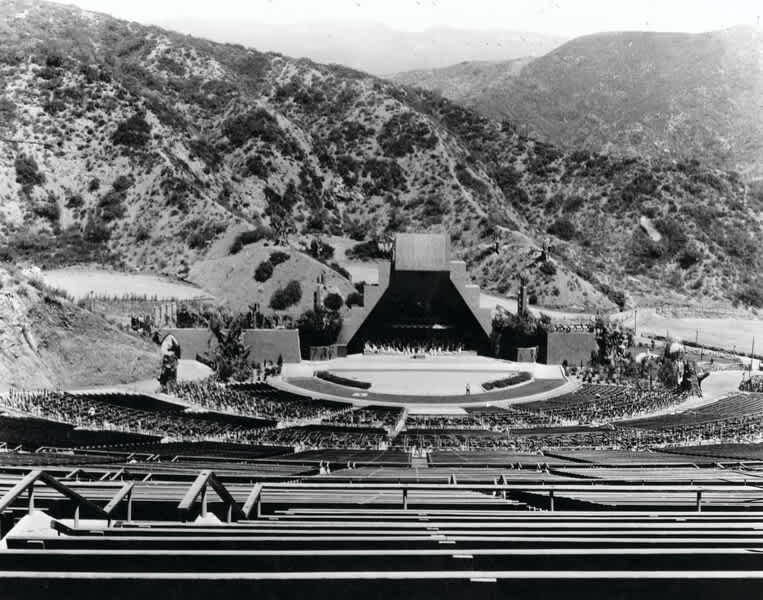

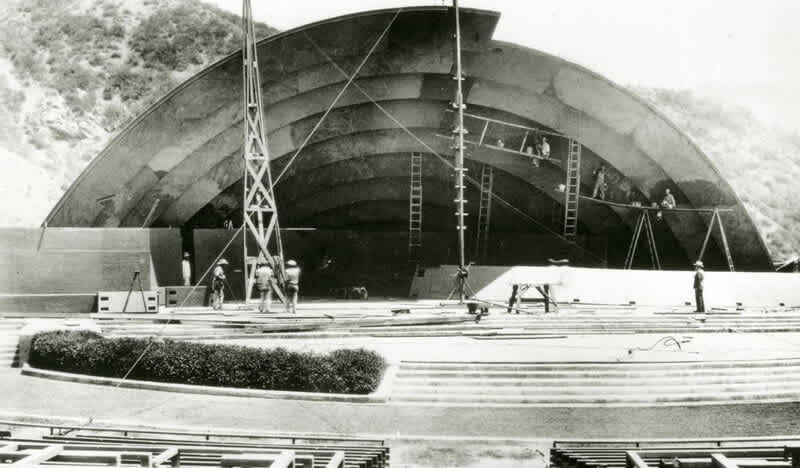

The Hollywood Bowl’s stage before the installation of the first shell in 1926

Photo Credit

Courtesy of Dr. and Mrs. George Thomason and family

The first Hollywood Bowl shell–designed by the Allied Architects in 1926 depicted naval scenes and Eastern imagery

Photo Credit

Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives

Lloyd Wright (son of Frank Lloyd Wright) designed the 1927 pyramid shell deemed “too modern” by the Bowl’s managers

Photo Credit

Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives

Lloyd Wright’s second shell (built in 1928) was composed of 9 wooden panels that could be assembled and disassembled in a day

Photo Credit

Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives

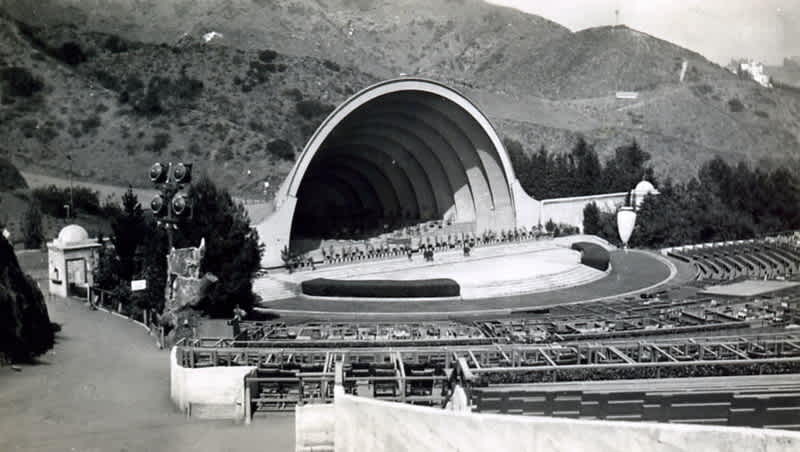

The 1929 semi-circular shell designed by Allied Architects became the iconic Bowl shell of the 20th century, lasting 74 years

Photo Credit

Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives

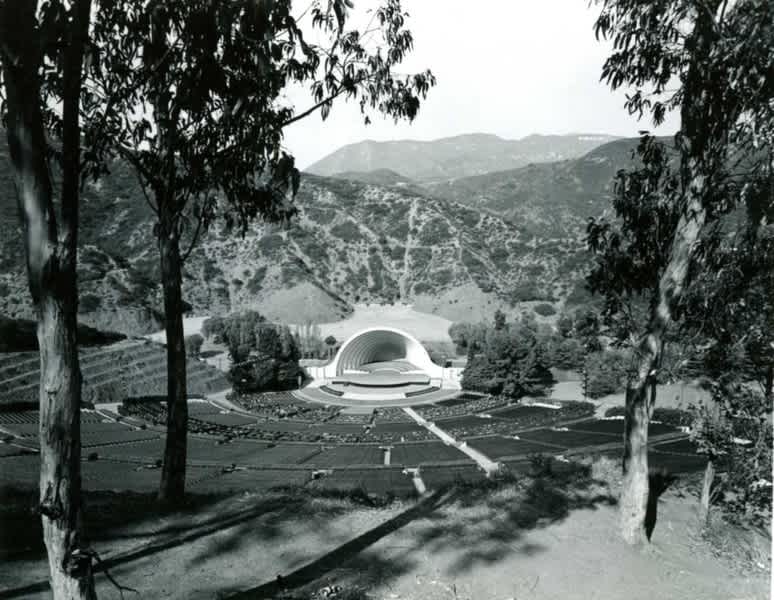

The 1929 Bowl shell seen from the back of the seating area

Photo Credit

Photo by Otto Rothschild Courtesy of The Music Center

The Bowl’s shell was modified in 1970 with “Sonotubes” designed by Frank Gehry, to help amplify and distribute sound.

Photo Credit

Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives

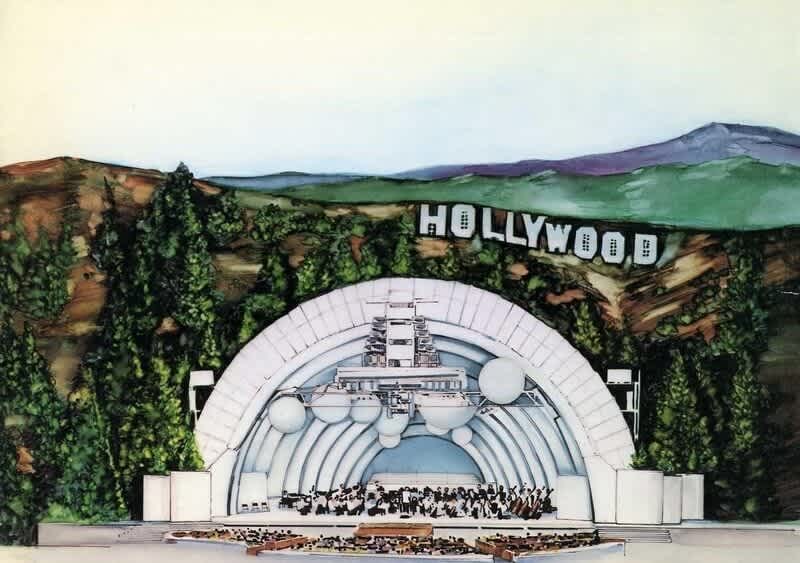

An artist’s rendering of the Bowl’s shells in the 1990s, with Frank Gehry’s “spheres” hung from the shell’s canopy.

Photo Credit

Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives

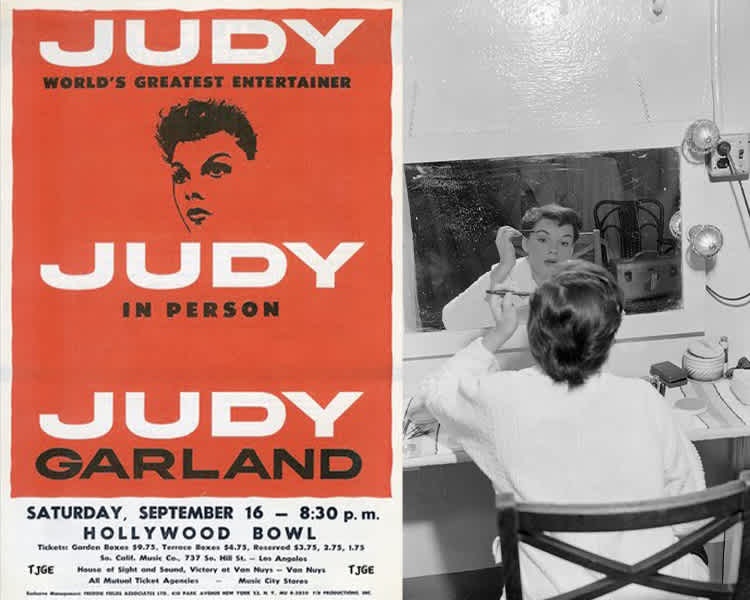

Judy Garland backstage before one of her many iconic performances at the Bowl.

Photo Credit

Photo by Otto Rothschild Courtesy of The Music Center

Bowl Principal Conductor Thomas Wilkins poses with the Blue Man Group before their concert in 2013

Photo Credit

Photo by Craig T. Mathew/Mathew Imaging

The Hollywood Bowl’s shell is lit up for a taping of a Sound/Stage digital concert in 2020

Photo Credit

Farah Sosa

1/12

I’ll be honest, until I started working here, I thought that the Bowl in the name Hollywood Bowl, referred to the bandshell. It always looked like a cereal bowl turned on its side to me. The Bowl name though refers to the natural shape of the canyon, Daisy Dell. In 1920 a choir leader named Hugo Kirchhofer looked around the canyon and said: “Why it’s like a big bowl. Hollywood Bowl.” The name stuck.

The Bowl’s shell—the one there today—was built in 2004. It’s the fifth in the Bowl’s history and by far the largest and most elaborate one.

The first three only lasted one season each—1926, 1927, and 1928. Each was disliked for a different reason. The 1926 shell, designed by a group of local builders named the Allied Architects, was a semi-ellipse that kind of looked like a Bowl shell that’s been squashed down on the top. The idea was to not block the view of the hillside, but in effect it really just blocked the natural resonance of the canyon, making it harder to hear the music.

The 1927 version, designed by Lloyd Wright (son of Frank Lloyd Wright), was better acoustically but was in the shape of a pyramid and was just too modern for people’s tastes. Wright said at the time that he had no idea why straight lines are modern and curved lines are traditional, but he acquiesced and built a curved shell in 1928.

Lloyd’s 1928 design was a real success, made of nine wooden panels that could be assembled and disassembled in a day. The panels themselves could be angled to “tune” the shell for performances. As far as we know, it sounded great, and it definitely looked great. Wright left instructions for it to be disassembled and stored in the winter after the season’s conclusion, but for reasons unknown, the shell was left out to rot and had to be bulldozed that spring.

In a matter of three months in spring 1929, the Allied Architects again designed a semi-circular shell made not of wood but of Transite, a mix of asbestos and concrete. It cost $50,000 and was supposed to be a “temporary” structure. It lasted until 2003 — that’s 74 of the Bowl’s 100 years! Even though it’s been gone for nearly two decades—the 1929 shell is really the shell that came to define the visual identity of the Hollywood Bowl.

Even though the fifth, current shell is 30% bigger, and has the big halo of lights and speakers hanging above it, it was built to maintain the feel of the shell that lasted most of the 20th century. In fact, a lot of patrons came back in 2004 and said they couldn’t tell the difference. The architects thought that was fantastic. They had kept the shell feeling like the cultural icon that it is.

Name a music legend, they’ve performed under one of the Bowl’s shells. Frank Sinatra. The Beatles. Prince. Ella Fitzgerald. Jimi Hendrix. If I had to pick one that I read and heard the most about in my research though—it was Judy Garland. She performed dozens of times at the Bowl, but in 1961, she was at the height of her powers as an entertainer. This is just a few months after her performance at Carnegie Hall was dubbed “the greatest night in showbiz history.”

A sold-out crowd of 18,000 stood in the pouring rain waiting for Garland to take the stage. Then-Bowl Superintendent Pat Moore said that normally in that much rain they would have canceled the concert, but there was no way they could get Garland’s diehard fans to leave the place, even if they’d tried.

For the performance, Moore had built an archway jutting forward from the stage so Garland could get closer to the audience and sing from above the reflecting pool that was in front of the shell. Rather than staying under the protection of the shell’s canopy, Garland strutted out onto the bridge in the pouring rain for much of the concert. As the shell was lit up in rainbow colors behind her, she sang her signature song—"Over the Rainbow.” Moore said, of the audience, “They lost their minds. They came unglued.”

When Garland strutted out onto the ramp, she looked out over the crowd and said, “Well, isn’t this an intimate little place.” The intimacy of the Bowl is remarked on by performers of all genres including the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra’s Principal Conductor Thomas Wilkins. Wilkins has that unique alchemy of musical ability and personality that electrifies on the Bowl’s stage. He’s said, “I’m a big believer in no labels music, and the Bowl is just like a giant version of how I live my life.”

Whatever the Hollywood Bowl’s programmers ask of Thomas Wilkins, his answer is usually the same: “Yeah, I’m game.” That was his answer when Program Manager Brian Grohl pitched him on a concert with the acrobatic Blue Man Group. Not only would Wilkins conduct the concert—he’d be a central character in the spectacle. The show’s producers had an idea: What if Thomas jumped over the shell, off an enormous crane, landing into a giant pool of blue paint?” Wilkins’ answer: “Yeah, I’m game.”

For insurance reasons, a stunt man swapped places with Wilkins before the big jump, so while the stuntman was jumping, Wilkins snuck backstage and had a bucket of blue paint thrown on him. Walking back out to the podium, he deadpanned to the audience: “Walked into here a Black man, walked out of here a Blue Man.”

Though created in controversy, the Bowl’s shell is now one of the most recognizable stages in the world. It’s on the County of Los Angeles’ official Seal. It’s been in hundreds of film and television shows. When musicians aren’t jumping over it, they are filling it with the soundtrack of summer nights, for 100 years and counting.

0:00

0:00