The First 000 Years

Presented by

Explore Episodes

![The Marquee]()

Play Episode

Episode 1 | 9:26

MARQUEE

Seeing your name on the Hollywood Bowl marquee is one of the milestones signaling you...

![Muse of music]()

Play Episode

Episode 2 | 7:21

MUSE OF MUSIC

Born of the Great Depression and nearly lost to disrepair, the fountain complex has s...

![Episode cover]()

Play Episode

Episode 3 | 7:28

PEPPER TREE LANE

Pepper Tree Lane—the walkway that transports you to the Bowl—is named for the trees t...

![Tea Room]()

Play Episode

Episode 4 | 5:35

TEA ROOM

For decades, the Hollywood Bowl’s tea room and gardens were a gathering place as mean...

![Hollywood Bowl Shells]()

Play Episode

Episode 5 | 7:37

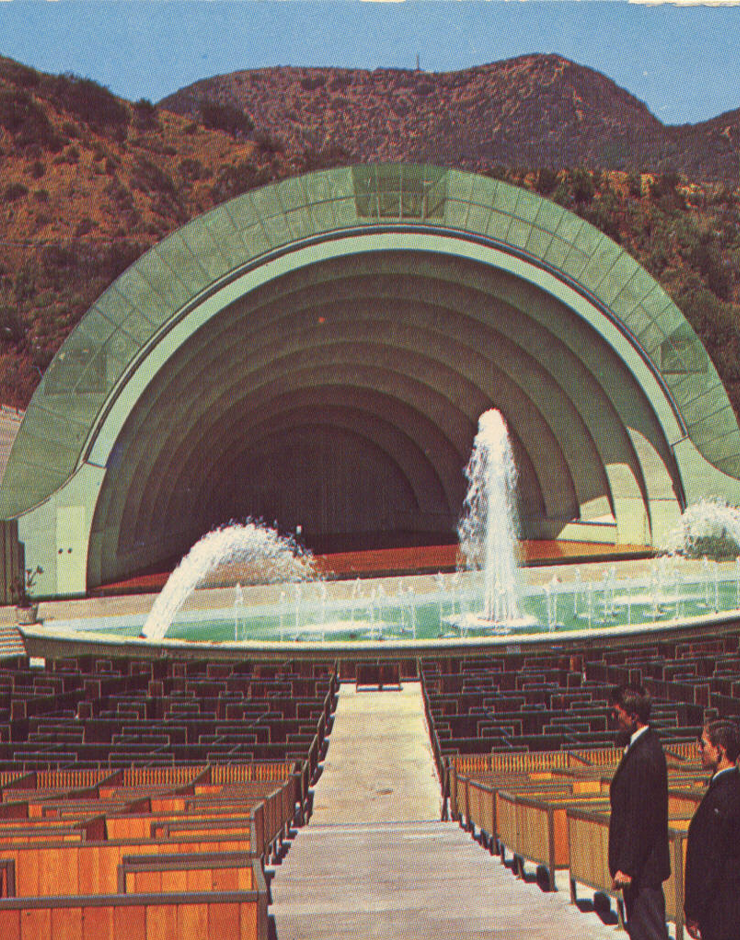

HOLLYWOOD BOWL SHELLS

From controversial choice to celebrated symbol, the Hollywood Bowl’s historic shells ...

![The Pool Circle]()

Play Episode

Episode 6 | 6:06

POOL CIRCLE

Of all the experiments in the Bowl design over the last century, none has inspired mo...

![SEATING AREA]()

Play Episode

Episode 7 | 8:22

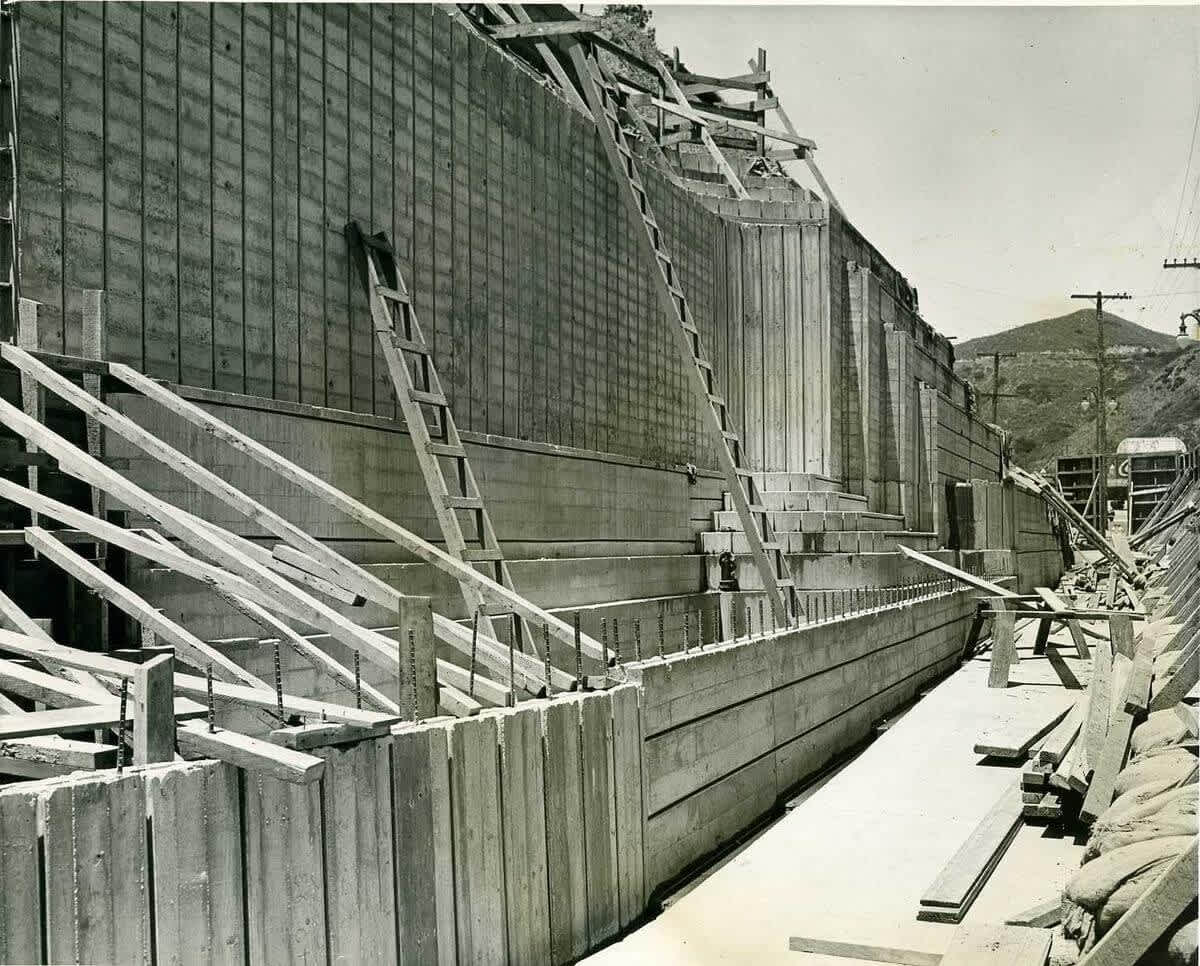

SEATING AREA

Whether you prefer a box or a bench, the Hollywood Bowl experience has been a beloved...

![Backstage]()

Play Episode

Episode 8 | 7:33

BACKSTAGE

Before the current shell was installed in 2004, backstage at the Bowl was more greene...

![The Park]()

Play Episode

Episode 9 | 8:46

THE PARK

The Hollywood Bowl is an 88-acre Los Angeles County Park, filled with picturesque hid...

![]()

Play Episode

Episode 10 | 12:13

NAMED SPACES

Only a handful of truly devoted Bowl fans have been honored with a space named after ...

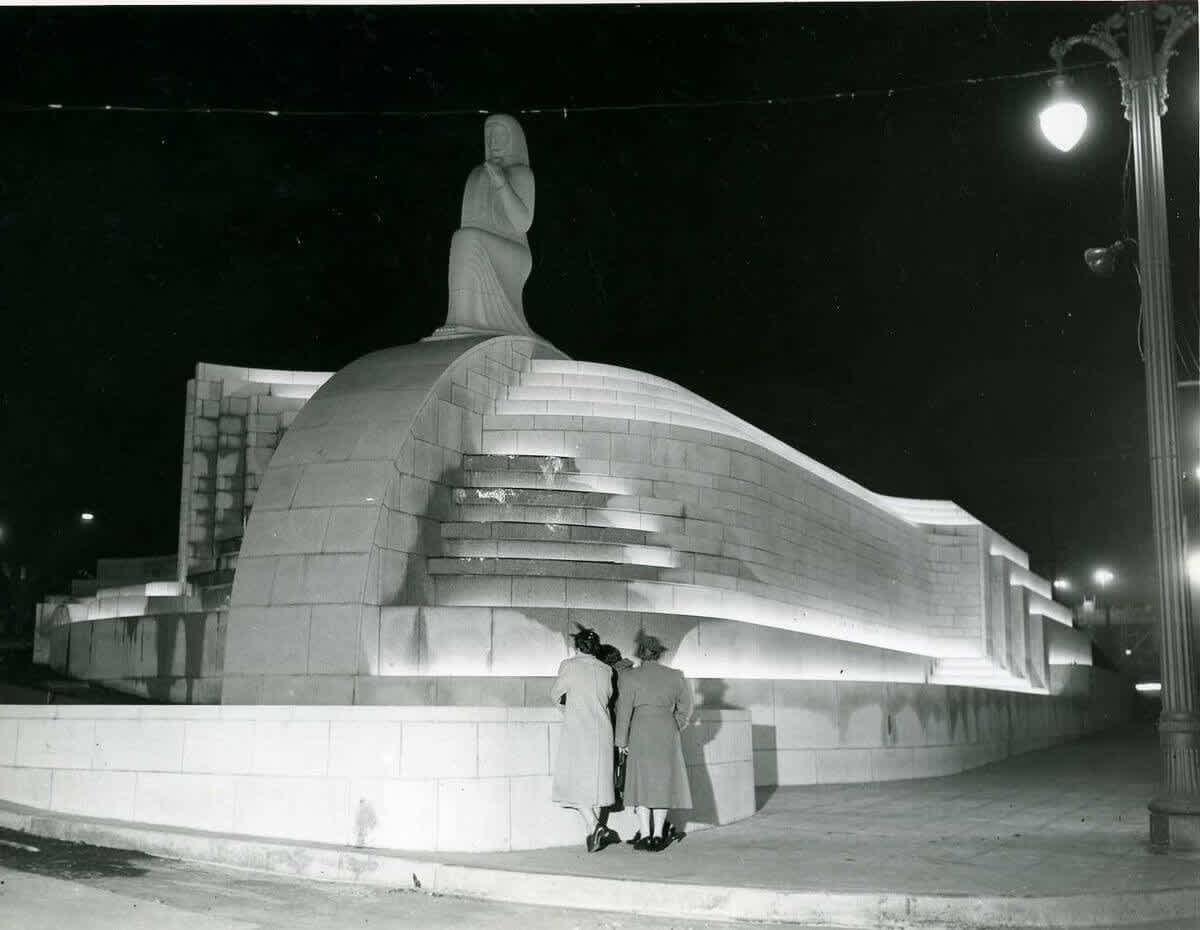

George Stanley’s Muse of Music, Dance, Drama, alit at dusk.

Photo Credit

Tom Bonner Photography

The Muse of Music fountain complex under construction, 1939

Photo Credit

Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives

Two admirers take in the Muse of Music statue, ca. 1940

Photo Credit

Photo by Otto Rothschild Courtesy of The Music Center

A woman steps out of a 1940 Ford, parked in front of the Muse of Music

Photo Credit

Hearst Newspaper Collection, USC Library

Muse of Music gets a powerwash, as part of the statue’s restoration, 2006

Photo Credit

Mark Ladd

Muse of Music fountain complex during reconstruction and restoration, 2006

Photo Credit

Mark Ladd

Close-up of the face of the Muse of Music, carved by sculptor George Stanley

Photo Credit

Mark Ladd

The Muse of Drama, one of the two smaller statues attached to the fountain’s base

Photo Credit

Mark Ladd

Restored fountains and lights, after 2006 unveiling; Muse of Dance in the background

Photo Credit

Tom Bonner Photography

1/9

As you first enter the Hollywood Bowl, off Highland Avenue, you may miss it, but look closely to your right and you will be greeted by a "statue." We call it a “statue,” but it’s actually three statues—all mounted on a 220-foot-long pedestal, which is itself a four-tiered fountain, illuminated by dozens of lights hidden inside.

Kneeling and strumming a lyre, the Muse of Music hovers above the entrance to the Hollywood Bowl on Highland Avenue. Statues of her two sisters, the Muse of Drama and the Muse of Dance, are perched below her, on either side of the fountain.

Built into the curve and slope of the surrounding hillside, the 1,000-ton structure practically disappears into the landscape. (At one point in its history, it almost did.)

Though you might not even notice The Muse on your first or second visit to the Bowl, once you stop and really take in sculptor George Stanley’s 1940 Streamline Moderne masterpiece, you can’t help but be drawn to this deceptively simple monument to the power of art.

As the Great Depression raged on in the late 1930s, the Hollywood Bowl continued to mount performances, but the facility itself had fallen into a state of disrepair. The Bowl’s leaders—its President Charles Toberman and the powerful County Supervisor John Anson Ford—lobbied for hundreds of thousands of dollars to restore the Bowl from the Works Progress Administration (W.P.A.)., FDR’s New Deal-era program to put Americans to work.

In 1937, Toberman used $125,000 in W.P.A. funds to hire sculptor George Stanley. He asked Stanley to build a work of public art, which he called a “fountain complex,” to mark the Bowl’s entrance. Stanley was most famous for designing the 13 and ½ inch Academy Awards “Oscar” statuette. He was also one of the designers of the Five Astronomers statue that towers above the nearby Griffith Observatory.

Unlike the Observatory, a paragon of Art Deco design, the Muse statue belongs to a lesser known off-shoot of Deco, Streamline Moderne. Simpler, more grounded, more horizontal, and more utilitarian, Moderne reflects the decade of the 1930s, as Americans found ingenious ways to economize without compromise.

The Muse was unveiled on July 8th, 1940, before the start of the Bowl’s 19th season. Though the community and country had been battered by a decade of Depression and were about to enter yet another world war, on that July afternoon, Ford cited the Muse as an example of the good that can be achieved when people work together for a common cause. He quoted, as he often did, his favorite author, Edward Everett Hale:

Look outward and not inward

upward and not downward

forward and not backward

and lend a hand.’

Ford went on to add: “To me, that is the important thing for the future of Bowl history—to lend a hand.”

Ford saw to it that all the construction workers and artisans who lent a hand on the project were given free tickets to attend the Bowl that summer. Hopefully some of them were able to see the highlight of the year—Igor Stravinsky conducting his own Firebird Suite, with choreography by the renowned Adolph Bolm.

The statue was an immediate success as the gateway to the Bowl, quickly becoming an icon celebrated on posters and postcards. But time was not kind to the Muses. By the late 1970s, pollutants and bird droppings eroded and discolored the surface of the sculptures. Mineral deposits built up in the fountain pools.

Weeds began to overgrow the fountain, and the Bowl’s managers, lacking the funds to do a proper restoration, planted hedges to cover up the statue which had become more of an eye-sore than an icon.

In the 1990s, George Stanley’s son, Maitland, lived in San Francisco. Once a year, he would drive down with his family to visit his favorite of his father’s works, bringing gardening shears to cut back the shrubs growing over his father’s name, which was etched into the Fountain’s base.

In 2006, the LA Phil and the County finally had the resources to do a major reconstruction project on the fountain, carefully restoring Stanley’s design to its original luster and adding modern waterproofing and plumbing upgrades. Maitland was in attendance for the second unveiling. He said, “People aren’t gonna believe that that enormous thing has been here this whole time!”

Not only was the Muse restored, but it became a defining structure for the Bowl architecturally.

At about the time of the Muses’ restoration, the LA Phil—in partnership with the County of Los Angeles—created the Bowl’s first Design Guidelines. The Guidelines, which are more than 150 pages, explore questions about what elements are historically significant within the Hollywood Bowl and propose strategies for how to preserve them.

Although they do not require and actually discourage building in a specific style, the guidelines identified Streamline Moderne as the Hollywood Bowl’s prevailing aesthetic. If you look around the Bowl today, you’ll see horizontal lines, rounded corners, natural embedded lighting, all these touches that come directly from Stanley’s creation and now give the Bowl a real Hollywood heyday vibe.

While it was built as a testament to the muses of music, dance, and drama, George Stanley’s 1940 creation has become a muse unto itself, inspiring 15 years of redevelopment at the Bowl, and delighting the thousands of audience members and millions of drivers who pass by it every day—if they happen to notice it.

0:00

0:00