The First 000 Years

Presented by

Explore Episodes

![The Marquee]()

Play Episode

Episode 1 | 9:26

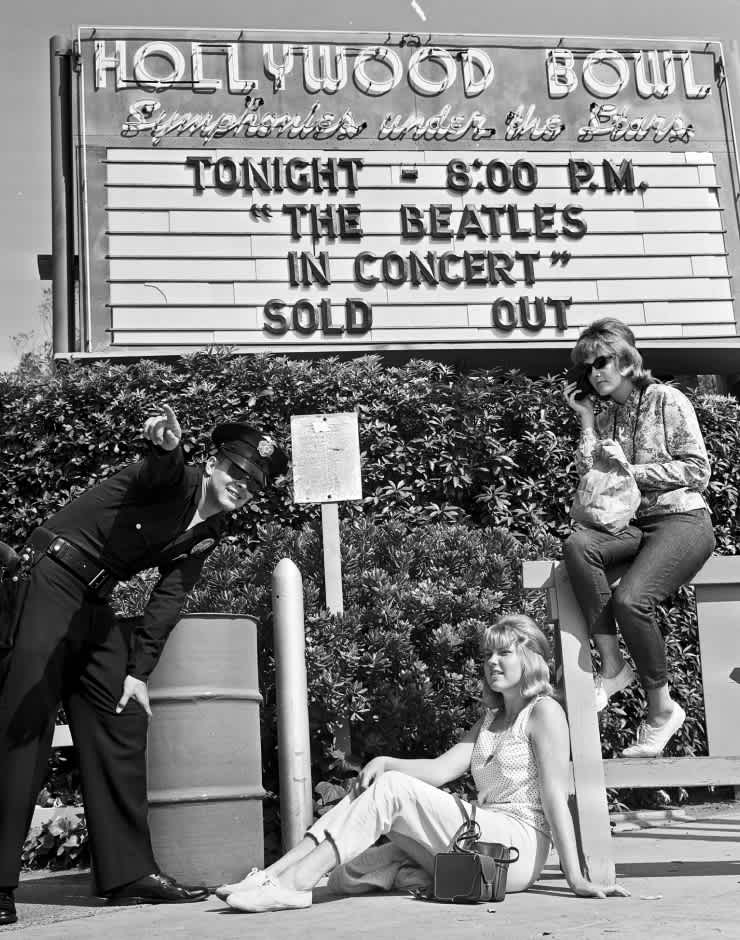

MARQUEE

Seeing your name on the Hollywood Bowl marquee is one of the milestones signaling you...

![Muse of music]()

Play Episode

Episode 2 | 7:21

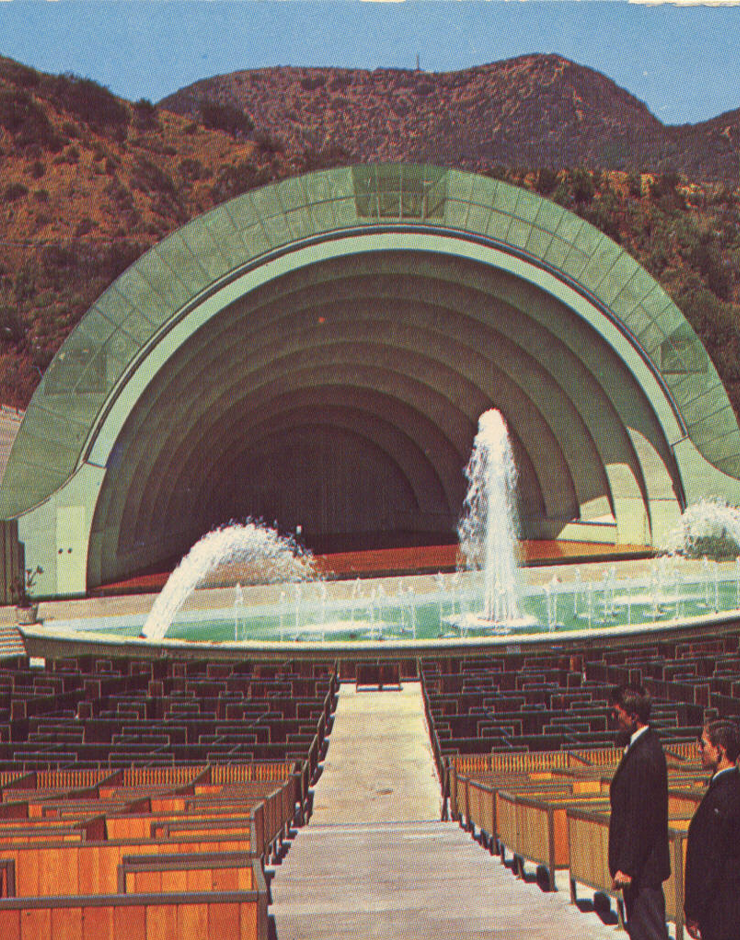

MUSE OF MUSIC

Born of the Great Depression and nearly lost to disrepair, the fountain complex has s...

![Episode cover]()

Play Episode

Episode 3 | 7:28

PEPPER TREE LANE

Pepper Tree Lane—the walkway that transports you to the Bowl—is named for the trees t...

![Tea Room]()

Play Episode

Episode 4 | 5:35

TEA ROOM

For decades, the Hollywood Bowl’s tea room and gardens were a gathering place as mean...

![Hollywood Bowl Shells]()

Play Episode

Episode 5 | 7:37

HOLLYWOOD BOWL SHELLS

From controversial choice to celebrated symbol, the Hollywood Bowl’s historic shells ...

![The Pool Circle]()

Play Episode

Episode 6 | 6:06

POOL CIRCLE

Of all the experiments in the Bowl design over the last century, none has inspired mo...

![SEATING AREA]()

Play Episode

Episode 7 | 8:22

SEATING AREA

Whether you prefer a box or a bench, the Hollywood Bowl experience has been a beloved...

![Backstage]()

Play Episode

Episode 8 | 7:33

BACKSTAGE

Before the current shell was installed in 2004, backstage at the Bowl was more greene...

![The Park]()

Play Episode

Episode 9 | 8:46

THE PARK

The Hollywood Bowl is an 88-acre Los Angeles County Park, filled with picturesque hid...

![]()

Play Episode

Episode 10 | 12:13

NAMED SPACES

Only a handful of truly devoted Bowl fans have been honored with a space named after ...

Musicians sit beneath the Bowl’s acoustical spheres, designed by Frank Gehry, 2003.

Photo Credit

Robert Millard

More than 20,000 attended to hear coloratura soprano Amelita Galli-Curci, perform with Alfred Hertz and the LA Phil in 1924.

Photo Credit

Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives

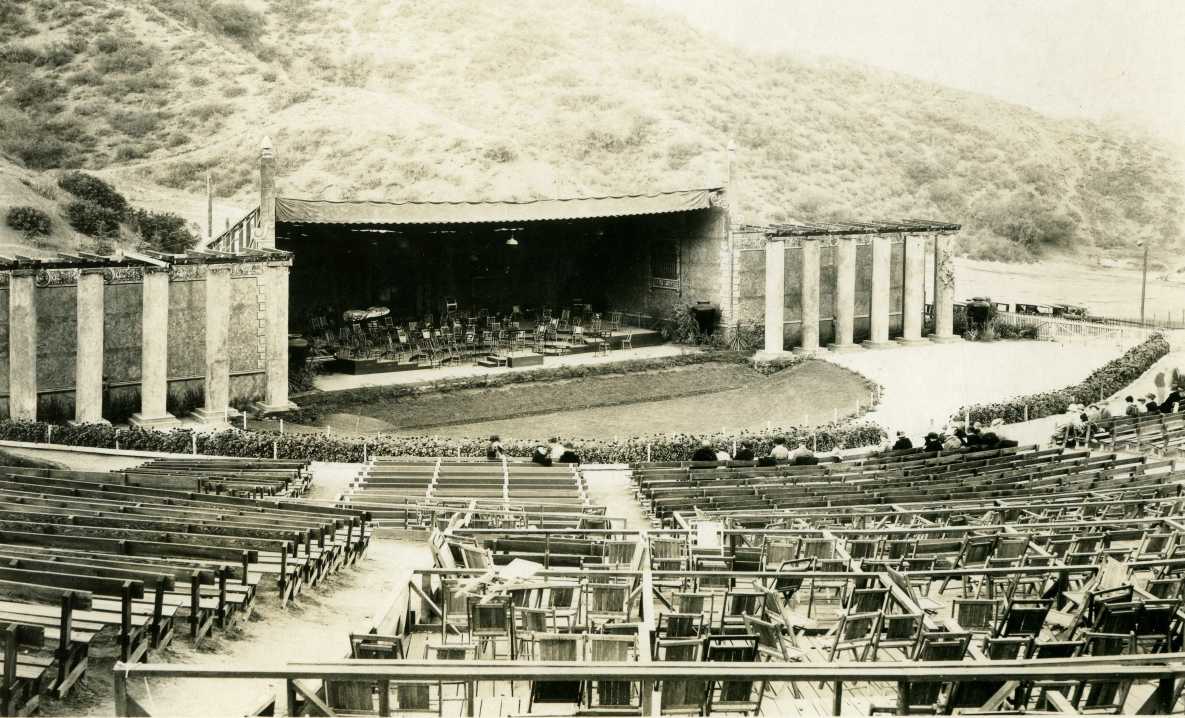

The Hollywood Bowl’s stage in the pre-shell era, flanked by Greek-style columns, 1923.

Photo Credit

Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives

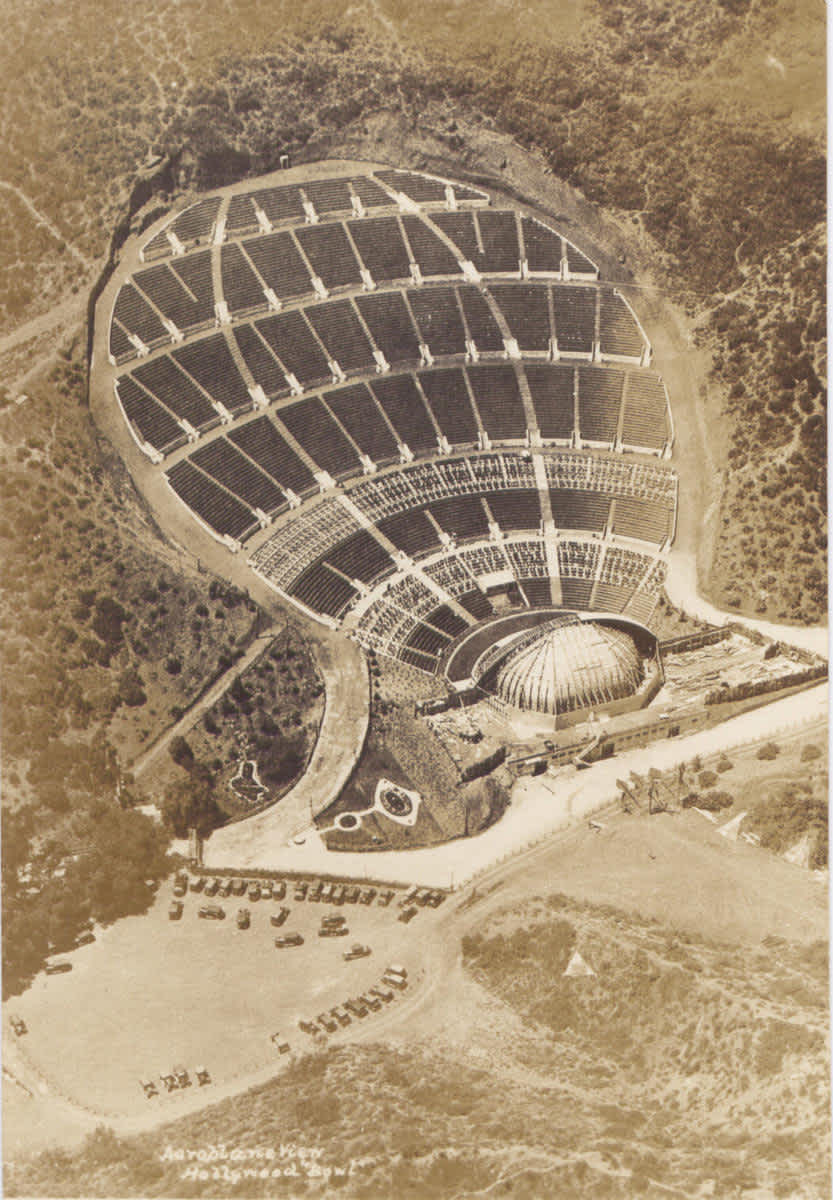

The Bowl’s balloon-shaped seating area under construction, photographed from the sky, 1926.

Photo Credit

Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives

A group of friends enjoys a picnic in the box seats, 1967.

Photo Credit

Photo by Otto Rothschild Courtesy of The Music Center

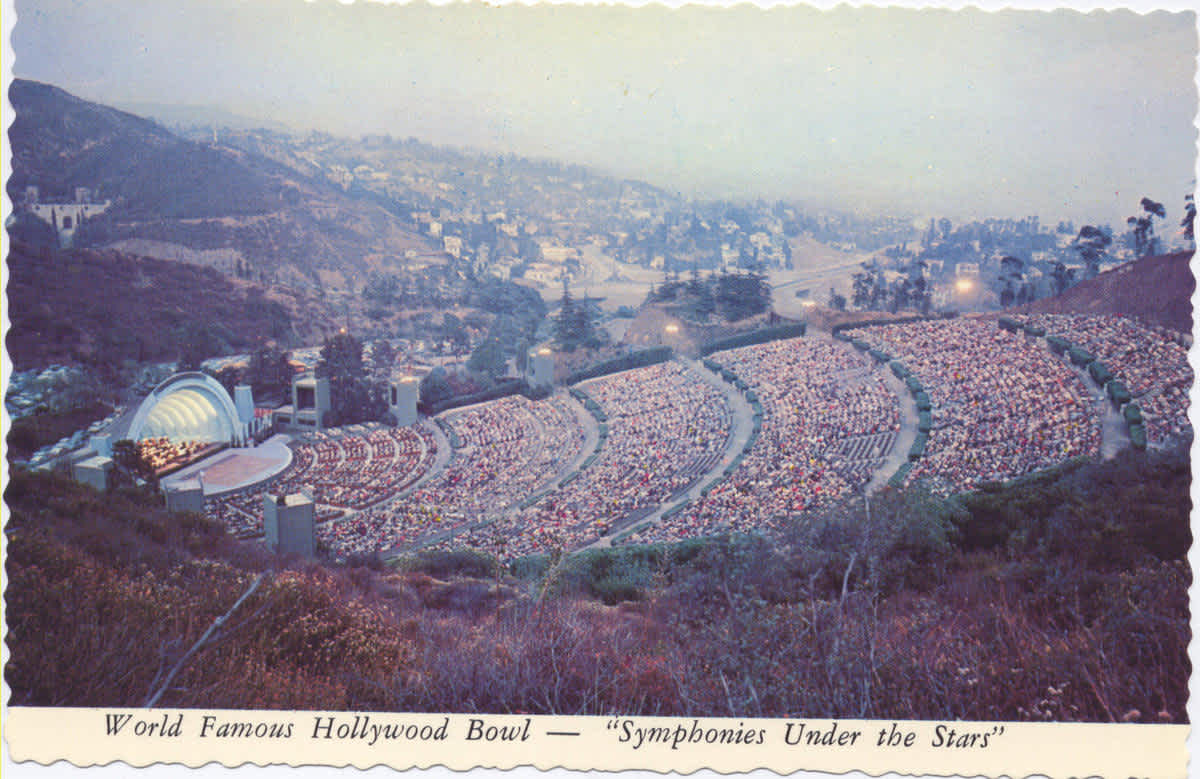

Postcard of the “World Famous Hollywood Bowl,” circa 1951.

Photo Credit

Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives

Audience members enjoying pre-concert dinner in the boxes, 2011.

Photo Credit

Photo by Adam Latham / Los Angeles Philharmonic

Audience members dancing during a KCRW Festival concert.

Photo Credit

Dustin Downing

Music lovers enjoying conversation before the concert begins, 2011.

Photo Credit

Dustin Downing

Audience members enjoy a perfect evening outdoors before their concert begins, 2021.

Photo Credit

Farah Sosa

1/10

As of the date of this recording, in spring 2022, the Hollywood Bowl is not on the National Register of Historic Places—which is kind of surprising. If you look up the list of places in Los Angeles that are on it—you’ll find elementary schools, movie theaters, post offices, an oil refinery—but no Hollywood Bowl. One of the reasons for that is that so much of the Bowl’s infrastructure has been built, torn down, and rebuilt again and again over the last century.

But one thing that has remained surprisingly stable is the seating area, the Bowl’s boxes and benches. The seating was designed and installed in 1926 and, with the exception of adding some more boxes and killing some benches for light towers, it remains essentially unchanged.

If you stand on stage and look out, the balloon-shaped house looks like it was fit to the hillside, but it was actually the other way around. The hillside was completely regraded to accommodate the seating area. Why is it shaped like a balloon? Because 100 years ago, Los Angeles’ most prominent architect just happened to love balloons.

Myron Hunt—like his more famous contemporary Frank Lloyd Wright—was a Chicago native who came up in the Prairie School of architectural design. Around the turn of the century, Hunt relocated to California and began working on significant projects in LA and Pasadena: the Huntington Library, Cal Tech, Mount Wilson Observatory, the Ambassador Hotel, and the Rose Bowl, among them.

Hunt loved the elliptical shape of a balloon, which to him suggested the uplifting and hopeful character of Southern California. The main entranceway to the Rose Bowl is Hunt’s most famous balloon, but his largest balloon (by a long shot) is the seating area for the Hollywood Bowl’s amphitheater.

The rows of benches in curving sections, the arcing cement staircases, and the cross-cutting promenades form a balloon that is lifting up from the Bowl’s stage and taking the audience to the stars above. To be ready for the summer season, construction began in March 1926. Three acres of land were regraded to prepare seating terraces—photos show the transitional period Los Angeles was in at the time—bulldozers and backhoes working next to horses and donkeys.

Humans, animals, and machines worked together to complete the 18,000-seat arena in just about three months’ time. While the wood of the benches gets replaced every thirty years or so, the undergirding steel framework is still very much what Hunt laid down that spring.

In addition to the aesthetic brilliance of Hunt’s design, there was also genius in his understanding of the social experience of the Bowl. The benches have always been affordable tickets for most shows, and because of the natural acoustics, you can hear as well in the last row as you can almost anywhere in the house. At the top, you can also see the Hollywood sign and The Ford theater across Highland. You can experience the Bowl in the full context of Los Angeles. You feel like you can reach up to the stars.

When researching the Hollywood Bowl book, I met a Hollywood couple—Philip and May—who are in their 80s. Philip has come to every Bowl rehearsal for the last 30 years. He lives in the neighborhood and walks over and sits up at the top and listens. When we replaced the benches a few years ago, he grabbed a bunch of wood to make a garden path for his front yard. When he comes to concerts at night, he likes the last row, because he says, “You can stand up and dance, and who wouldn’t want to dance? From up there, we feel like the king and queen of Hollywood.”

Of course, the other Bowl experience is no less magical. Bowl boxes are like family heirlooms, passed down from generation to generation. Philanthropist and business leader Dorothy Chandler, who revamped the Bowl in the 1950s, turned Bowl picnicking into a high-status affair with candelabra, silverware, and wildly elaborate meals.

The LA Times (published by her husband) would run a special multi-page spread each June with “Bowl fashions” for the upcoming summer and the most of-the-moment picnic recipes, often submitted by LA’s elite families and celebrities. Having a Bowl box became a symbol of status—Charlie Chaplin had his favorite in the 1920s, Walt Disney had his favorite in the 1950s.

But not every well-to-do family were culinary experts. George Randolph Jr. who was the grandson of William Randolph Hearst—one of the richest men in the world, would actually hit up KFC on his way to the Bowl, but he was too embarrassed to walk in with the bucket, so he’d transfer the greasy chicken into a picnic basket before carrying it to his box. His son Stephen, who still comes to the Bowl, told me that amazing story when I interviewed him.

Of course, there is also quite a tradition of patrons enjoying both boxes and benches, sometimes in the same night. The Bowl’s open aisles almost compel it. One account, perhaps my favorite description of the power of the Bowl, came not from a concert but from a memorial held days after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.:

In a letter to the LA Times in 1995, Compton resident Steven Cohen reflected:

“In 1968, I attended a memorial for Martin Luther King that was held at the Bowl two days after he was assassinated. I was 19 and I went with friends who, like me, were young, emotional liberals. They had an incredible lineup of R&B performers—everybody from Aretha Franklin down was there. We got in on general admission tickets, then snuck up front and sat in a box with a wealthy Black family from Hancock Park.

This was a solemn day, but it was also a day of solidarity with other human beings regardless of background, and the racial mix of the audience was half black and half white. I think the spirit of that day had to do with the setting of the Bowl because there’s a real potency to being outside in the open air. Because we couldn’t make sense of it, we needed to be with others who shared the sense of uncertainty we felt.”

After 100 years, the seats at the Bowl still look like a natural evolution of the landscape. As Myron Hunt said at the time: “We must accept the wilderness and use it as the background for our picture, the setting for our jewel.” Sit in a box, a bench, or both—there’s no wrong way to experience the Hollywood Bowl.

0:00

0:00